GRAD® Pinot noir Clone 1 Series in Brief:

- This unique GRAD® clone series was developed from meristem-cultured explants made using state of the art techniques applied to material from my foundation U.C.D.5 Pinot noir mothervines. These in turn were made from material from U.C.D.5 Pinot noir vines in the old Blands national foundation block in Hamilton. Those vines, in turn, derive directly from the 1970s import of U.C.D.5 by Dennis Irwin.

- As far as I know, this meristem cultured explant series is not only a world-first for U.C.D.5 Pinot noir, but is still unique in the world also. (Foundation Plant Services at U.C. Davis has meristem-cultured the pre-thermotherapy ‘parent’ / source of U.C.D.5 Pinot noir — the U.C.D.4 clone — to make U.C.D. / FPS 91. So the GRAD® clone 1 Pinot noir series is the ex-U.C.D.5 parallel of this new UCD meristem cultured clone.)

- I have grown and studied the meristem-cultured GRAD® clone 1 Pinot noir series for nearly 10 years now, and with one or two exceptions (which have been excluded from the Clone 1 series, and which appear to be strictly post-tissue-culture mutations) these explants have given replicates which are ampelographically quite similar to U.C.D.5. Certainly, the selected GRAD® clone 1 Pinot noir series vines are the Rolls Royce version of the already extremely fine U.C.D.5 Pinot noir clonal line.

- The GRAD® Clone 1 series has high robustness, very high vine health, and mostly produces at crop levels closely similar to U.C.D.5 Pinot noir. These vines’ ripening period appears to be about the same, or perhaps 3 to 4 days earlier, than U.C.D.5, and is thus comparable to Dijon clones like B114 and B115.

- Typical well managed vines in this genetic line give wines that are characterised by black cherry and violet aromas reminiscent of fine Burgundies from Vosne-Romanée, with a distinctly plush palate dominated by the black cherry fruit heralded on the nose. Good fruit exposure from early leaf-plucking of the fruit zone post-flowering will allow picking at the optimal 23 Brix level where this genetic line is typically ‘a point’. As with many Pinot fine Pinot noir clones, acidity falls away and pH rises after 23 Brix, so delayed picking and so-called ‘extra ripeness’ (especially beyond 24 Brix) should be handled with very great caution, particularly where whole bunch fermentation of this clone-series’ fruit (which very much suits it) is to be employed.

- Vines grafted with GRAD® 1 Pinot noir series scions will be available in New Zealand through Stanmore Farm nursery under license from GRAD® from 2022 onward depending on bulking up of mothervines in their nursery. Advance orders for this world-exclusive Rolls Royce material may be placed now.

- E-mail for orders or inquires: orders@stanmorefarm.co.nz

Phone: 0800 Stanmore (0800 782 666)

Website: stanmorefarm.co.nz - Mobile: 027 544 0140

- For further information and advice on the suitability and use of this clonal line in your vineyard, contact Dr. Gerald Atkinson at grapevines@hotmail.co.nz

- A comprehensive non-propagation contract must be signed off as part of your purchase order.

- Click here to download single A4 page PDF ‘In Brief Fact Sheet’ on GRAD®1 Pinot noir clone series

Source

In the early-2000s I was fortunate enough to be able to obtain high health propagation material derived from one of the original U.C.D.5 Pinot noir mothervines in the old Blands National Foundation Vineyard at Hamilton. (These foundation vines were planted on their own roots and came directly from material propagated from the original U.C.D.5 Pinot noir imported from U.C. Davis by Dennis Irwin in the mid-1970s. I have also been able to precisely track down the source of this material: U.C. Davis Foundation Plant Services’ officer Nancy Sweet has told me that “Mr. Irwin placed an order in 1974. In Spring 1975, we sent him … 6 cuttings of Pinot noir 05 (from location FV F7v12)….)

After growing the ex-Blands Foundation Vineyard U.C.D.5 material for a number of years, the opportunity arose ca. 2010 for me to have shoot tips from the cream of these vines experimentally meristem-cultured as part of an attempt to test and establish a non-mutational meristem-culture protocol for Pinot noir. As I understand it, the success of the technique was later confirmed (by whole-of-genome comparison of pre- and post- tissue culture material from my mothervines). I subsequently received around 40 explants made using this new procedure, and over the last ten years or so I have trialled them, made 1st and 2nd generation re-selections, and have begun to bulk-up the very best performing lines.

All the vine stock in the GRAD®1 clone series is, to the best of my knowledge, the only meristem-cultured, or re-selection of meristem-cultured, line of U.C.D.5 Pinot noir in the world at present. Foundation Plant Services at the University of California at Davis have meristem-cultured the pre-thermotherapy ‘parent’ of U.C.D.5, viz., Pinot noir U.C.D.4 (and re-identified this m.c. line as ‘U.C.D.91). However — and most remarkably in my opinion — they ceased some time ago to hold or propagate any lines of U.C.D.5 or U.C.D. 6 Pinot noir, apparently — and highly erroneously — believing that these two ex-thermotherapy ‘offspring’ of U.C.D.4 are genetically identical both with it and thus also with each other. This is a remarkable error of judgement, as the three clonal lines in question are so demonstrably different that it is easy for an experienced ampelographer familiar with each of these clones to distinguish them in one and the same vineyard. Moreover, each of these three clonal lines produces different kinds of wine and ripens differently: U.C.D.4 gives dark red cherry -fruited wines with considerable flesh and spiciness; U.C.D.5 ripens perhaps a few days later and gives distinctly black cherry -fruited fleshy and plush wines suffused with aromas of violets; and U.C.D. 6 ripens up to 10 days earlier than U.C.D.5 and up to 7 days before U.C.D.4 and gives mid-red cherry wines suffused with ‘petit fruits rouge’ aromas and flavours. But despite these utterly real differences, only U.C.D.91 (the meristem-cultured version of U.C.D.4) now holds a place in the Foundation Plant Services collection. As a consequence, it is no exaggeration to say that the GRAD®1 clone series is the currently unique-in-the-world parallel to U.C.D.91; it is distinguished of course by being derived from U.C.D.5 Pinot noir.

In California in particular, but also in Oregon, and to a much lesser extent in Australia and N.Z., the U.C.D.4 -6 clone series has been popularly re-christened as ‘Pommard’. (In this country, the clone series is very mistakenly referred to my many as ‘Clone 4’, ‘Clone 5’, and ‘Clone 6’, but there is absolutely no such (implied) international or otherwise solely numerical clonal number system across all of a variety’s clones any- or everywhere; the clones in question are U.C.D. (or F.P.S.) 4, 5, and 6.) Until very recently, it has been widely held that their American designation as ‘Pommard clones’ derived from the fact that this material was obtained by Harold Olmo from Château de Pommard in 1951. However this is not factually correct. The true account recently emerged in a definitive and highly informative article by U.C. Davis’s Nancy Sweet. This was web-published in July 2018 for U.C.D. Foundation Plant Services as “Pinot: A Treasure House of Clonal Riches” / https://fps.ucdavis.edu/grapebook/winebook.cfm?chap=PinotNoir . In this article, Ms Sweet revealed that Olmo in fact selected his ‘Pommard’ Pinot noir material from the “Les Croix” vineyard in Pommard in 1951.

Close examination of the various extant Pommard climats in fact reveals however that the identity given in Olmo’s collection notes, and which Nancy Sweet accordingly cites, involves a misnomer on Olmo’s part: there is no such vineyard as ‘Les Croix’ in the Pommard appellation. Rather, of the 28 Pommard premier cru climats, the source must surely have been Les Croix Noires, although there are two further similarly-named Villages ‘Lieux-Dits’ allowed on labels, viz.: La Croix Blanche and La Croix Planet. The nearest match is nevertheless ‘ Les Croix Noires’, and as it has long held premier cuvée / premier cru status (even before the phylloxera era), it seems most likely to be the vineyard from which Olmo obtained his Pinot noir material.

As Nancy Sweet tells us,

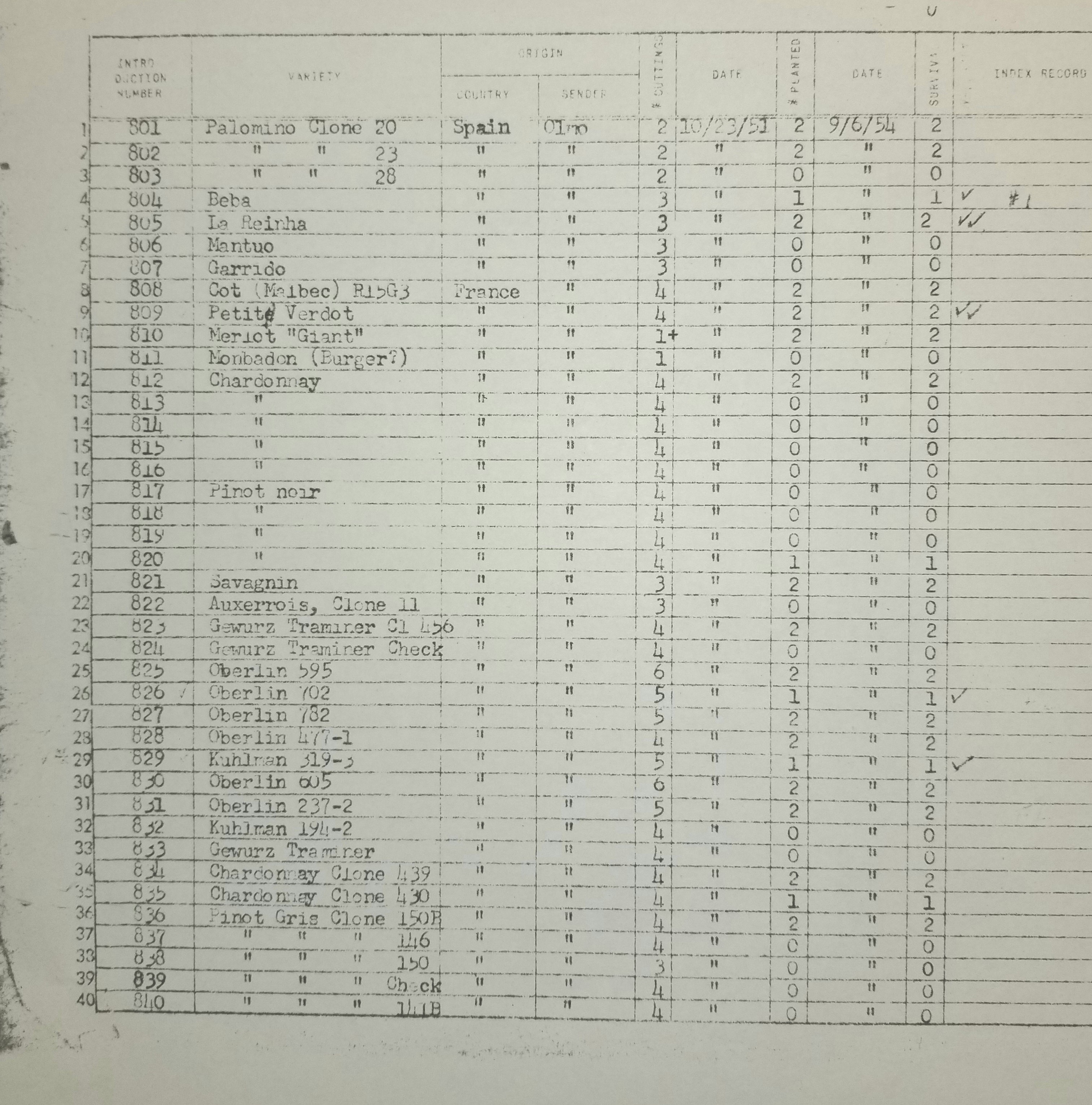

Olmo selected [cuttings from] four vines on October 11, 1951 , from what he identified [in his notes] as the “Les Croix Vineyard, Pommard, France”. …. A binder containing a record of the grape introductions … [then] shows that four selections named Pinot noir arrived at Davis on October 23, 1951. The record reflects that Olmo caused the cuttings to be sent to Davis from France. Four separate groups of four cuttings per group appear in the binder. Olmo assigned a separate collection number for each set of four cuttings. The four Pinot noir selections were given “Introduction numbers” 817 through 820. The only one of the four selections that survived the shipping and testing process was Pinot noir number 820. After completion of index testing in 1954, that selection appeared on the 1956 list of registered grapevines at FPMS as Pinot noir-1 (location O.F. 9 v 9-11). Its origin was described as ‘820 Pommard, France’.

The records held at U.C. Davis Foundation Plant Services original record of the one single cutting which survived can be seen in the following record book page image:

The original U.C.D. ‘Pommard’ material thus derives from a single cutting, and of course from a single vine. However, the detailed account given by Nancy Sweet, as highly useful as it is, still raises many important questions. Not least of them are how and why Olmo came to select Les Croix Noires in Pommard as the source of his cuttings. We know he was keen to obtain only high health vine material, and the subsequent history of virus testing of the U.C.D. Pommard line clearly shows that this was indeed what he sourced (from this particular vine at least). But it needs to be remembered that such material was extremely scarce in Burgundy vineyards even by 1951: infection by leaf-roll viruses and fan leaf (and related nepo-) virus was extremely common. The so called ‘Dijon clones’ nos. 111 – 115 that were sent to the Colmar Research Station in 1960, and which were then selected by Raymond Bernard, came from Domaine Ponsot in Morey St. Denis and were the result of rigorous visual selection during the 1940s and 50s. Virus was rampant and epidemic in mid-20th century Burgundy vineyards, so the Domaine Ponsot project was both ambitious and far-sighted, but it also underscores the extremely high likelihood that Olmo did not go to Pommard’s Les Croix Noire climat and obtain clean material there by mere accident. In short: there is still more to be uncovered in the account of the origins of the U.C.D. / F.P.S. Pommard genetic line. Currently, I am seeking to enlist the aid of one of Burgundy’s leading vineyard and vineyard-owner historians to throw further light on Olmo’s connection to the owners of the specific part of the Les Croix Noires vineyard from which he obtained his cuttings.

Health status

The GRAD® 1 Pinot noir series is derived entirely from multiple-PCR-tested mothervines which have all been shown only to have a weak strain of the benign RSPaV1 virus. However, meristematic tissue culture is highly effective in eliminating all viruses from vine material because it selects from only a tiny mass of cells right at the shoot tip where virus infection is by far least likely to occur. Consequently, I fully expect that further PCR testing of the GRAD® 1 Pinot noir series will confirm their free of detectable virus status. In the meantime, E.L.I.S.A. testing of vines in the series for GLRaV1,2,3, and GVA has consistently returned negative results, and testing for GLRaV3 will be ongoing of course at Stanmore Farm as part of the N.Z. Grafted Grapevine Standard protocols.

Characteristics

It was the fundamental intention of the project which produced the GRAD®1 series explants that they should be genetically identical to their pre-tissue-culture U.C.D.5 parent. In the very few instances where there have turned out to be clear differences between the meristem-cultured explants and the original U.C.D.5 Pinot noir source material in the GRAD® vine collection, I suspect they chiefly result from the ultra-high-health state of the latter material. Thus it appears that the m.-c. explants generally have enhanced vine robustness and probably also slightly earlier ripening (by about 3 days). The very thorough viral and non-viral pathogen ‘clean up’ that meristem culture tends to effect is probably the cause of this, I suggest. I do nevertheless have at least one distinctive mutant line which derives from this explant series, but I very strongly suspect that its mutations are the result of post-tissue-culture conditions and causes. The appearance of this explant in its first 7 or 8 years in the GRAD® R&D nursery was consistent with all the other explants; its distinct mutation only occurred after it was pruned right back to just 2 buds ca. 2019, and it seems that what then grew on from this basal bud pair was the result of a strong epigenetic variant response that has produced very considerable apparent mutation. (See the entry in this website for the GRAD® Pinot noir précoce line which I currently have under development and which comes from this explant.) More generally speaking, I suspect that because meristem-culture uses only L2 layer (inner) tissue (from the inner portion of the extreme growth end of shoot tips), the explants that result from it may well carry over very few, if any, epigenetic inheritances from their pre-meristem-culture parent vine. This should be particularly significant for a variety like Pinot which is very highly phenologically responsive to environmental conditions. These responses seem to be connected in Pinot with a range of ‘gene switches’ and other epigenetic responses which cause variations in, for example, leaf shape, leaf and shoot hairiness, the shape and depth of leaf teeth and leaf sinuses, berry skin thickness and toughness, and in the type of polyphenols that develop in the fruits’ pips and skins in response to in-vineyard conditions. If my hypothesis is correct, a meristem-cultured Pinot explant effectively may enter its post-tissue-culture vineyard environment as an epigenetic ‘blank slate’ because responses to the vineyard environment are of course mediated very much through the vine’s outermost, L1, tissue layer, and meristem-culture completely dispenses with this cell material in regenerating the vine.

In all then, the GRAD® Pinot noir Clone 1 Series opens up both new ultra-high-health horizons for the U.C.D.5 clone, and introduces new potentially very high quality clonal variants of this line as well, some being just subtly different, while some are more are markedly so. Because of the clear overall merits of the range of the best explants produced by this meristem-culture experiment, I have decided not to release just a single explant clone but rather a select group of closely similar ones. If and as more distinctive variants and variations become evident, I may nevertheless either re-identify a given clone within the wider group (as a specific sub-clone) or reclassify it under a completely separate clonal identity (as, for example, is the case with the GRAD® Pinot noir précoce clone that is presently undergoing further observation and bulking up).

Because of their fairly close general morphological and phenological similarity to U.C.D.5, it’s fair to say that growers experienced with that clone will find the GRAD®1 clone series a highly suitable ‘Rolls Royce’ version. Ripening may be a few days earlier, and the vines are somewhat more robust and should therefore be well-tolerant of careful non-stressing restriction by close planting (ideally at 5,000 vines / ha.), managed deficit irrigation, and strict control of vine nutrition (where you give only what is required when it is required, and no more). Planting in sheltered hillside sites with minimal wind exposure (especially from nor-west winds in Martinborough, Marlborough, North canterbury and Central Otago), is of course an absolutely fundamental requirement to bring out the best in any Pinot variety, but especially so in Pinot noir (because of the correlation between vine stress in the variety and the production of short-chain, bitter and hard, catechinic tannins in the skins and pips, along with mean pinched fruit aromas and flavours). In short: in top sites with skilled management and close-planting, the GRAD®1 Pinot noir clone series should produce fruit of exceptionally high quality.

Qualitative potential

Both in Australia and N.Z. I have found that the most astute Pinot noir producers are well aware of the very real limitations and shortcomings of the so-called ‘Dijon’ clones and have long-since ceased to fawn over them as if no other clones could be, or ever were, better. In particular, it is remarkable how often U.C.D.5, and the U.C.D. ‘Pommard’ line in general, are noted by these very astute producers as clearly both under-rated and superior. As the chief viticulturist for the company that has some of the biggest Pinot noir plantings in Victoria and Tasmania said to me not long ago, if one clone really stands out, it’s not any of the Dijon clones, but it’s U.C.D.5, with U.C.D.4 close behind. In short: hype is one thing; class is altogether another — and the U.C.D. ‘Pommard’ Pinot noir genetic line has class in spades.

I rate U.C.D.5 as quite simply one of the finest modern Pinot noir clones ever released, and I know top Australian Pinot noir producers, and a few in this country too, who entirely agree. (They also all share a healthy awareness that the ‘Dijon’ clones’ reputations are largely hype, not substance.)

I well remember two Burgundy pieces of 2002 Mountford Pinot noir that were entirely made from the very best U.C.D.5 fruit I produced there. Despite C.P. Lin’s baseless and dogmatic insistence that all the fruit must be picked at not less than 24° Brix, the cool 2002 Waipara vintage (which was in fact picked by me at no more than 24º Brix — despite the fact that it was fully ripe at 23º) retained sufficient acidity and low pH before malo-lactic conversion to produce two Burgundy pieces of quite exceptional young 100% U.C.D.5 Pinot noir. Their emulation of young Vôsne-Romanée was remarkable: made from vines I had dry-grown all season, with fruit fully exposed from fruit-set onward, the young mono-clonal wine had intense black cherry and violet aromatics and a complimentary flavour spectrum carried on a superb palate with plushness, length, and balance. Alas, after malo, these pieces’ quality was never the same however: their original pH was in fact revealed as sitting on a knife edge, and post-malo it had moved to too high a level and the once superb young wine had lost its acid balance and liveliness. If only picking at 23 Brix had been possible, but under C.P. Lin it was deemed utterly unacceptable — and the consequences in squandered wines of quality spoke for themselves (to me at least). But despite these woes and depredations, the cat was nonetheless out of the bag as far as I was concerned: U.C.D.5 was revealed as a stunningly good clone if it was handled correctly in the vineyard; the remarkable Vôsne-Romanée similarities were etched in my memory. By the time I quit Mountford in 2005, in abject disgust at the massively alcoholic and heavily acid-adjusted wines being produced, I had made it my business to obtain U.C.D.5 Pinot noir vine material that had direct provenance to the original National Foundation Vineyard, Blands, planting. This was rather hard, but not impossible, to come by in the early 2000s (as the block in question was in a shocking state of deterioration and neglect), and eventually, via this source, I obtained and grew the three 1st generation, P.C.R. tested, D.N.A.-identified mothervines in the GRAD® r&d nursery from which in turn the GRAD®1 meristem-cultured Pinot noir clone series was made.

Ripening period

The clones in the GRAD®1 Pinot noir series either ripen their fruit at the same time as ‘standard’ U.C.D.5 or about three days earlier. Ripening times are thus comparable to the B114 and B115 ‘Dijon’ clones, all else being equal.

Availability

Stanmore Farm nursery will have increasing numbers of mothervines of an increasing range of the clones in the GRAD®1 Pinot noir series from 2021-22 onward. Budwood should be available in increasing volumes therefore from 2022 onward.

Inquire directly to Stanmore Farm Nursery for further details and to place forward grafting orders:

Website: stanmorefarm.co.nz

E-mail for orders or inquires: orders@stanmorefarm.co.nz

Phone: 0800 Stanmore (0800 782 666)

Mobile: 027 544 0140

For more information about these clones, and for details regarding their use in, and suitability for, your vineyard, e-mail Dr. Gerald Atkinson at: grapevines@hotmail.co.nz

Please note that a strict and comprehensive non-propagation contract must be signed off as part of your purchase order.

GRAD® is a New Zealand registered trademark uniquely and exclusively used to identify the vines in the GRAD® vine collection. Use by unauthorised parties to identify any vine material, or other use for commercial gain, is an infringement of this trademark.

Genetic ‘fingerprinting’ and clonal traceability

Vine pirates BEWARE! It is now possible to genetically fingerprint, uniquely identify, and individually detect grapevine clones using the latest-developed molecular genetic sequencing techniques. See the breakthrough research paper by Michael J. Roach et al, “Population Sequencing Reveals Clonal Diversity and Ancestral Inbreeding in the Grapevine Cultivar Chardonnay”, published November 20, 2018 at

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1007807